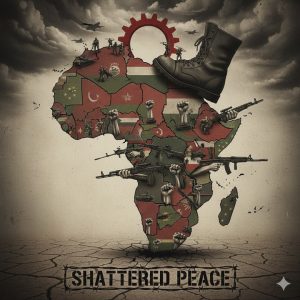

It is hard to ignore how deeply military coups and attempted takeovers have come to define Africa’s political narrative in recent years, evolving from shocking aberrations into a disquieting regional pattern. This arc of instability, stretching from the arid expanses of the Sahel to the resource-rich coasts of the Gulf of Guinea, has reached nations once considered democratic anchors, rewriting the rules of power and public trust.

The turbulence of 2025, a year marked by forceful seizures of state television stations, midnight declarations on national radio, and the swift dissolution of constitutions, bled directly into the new year. A mere four days into 2026, the thwarted assassination plot against Burkina Faso’s Captain Ibrahim Traoré delivered a stark, dual message: the tremors of a takeover do not end with a successful putsch, and the regimes they birth face perpetual threats from within. This event underscored the entrenchment of a new political reality across the Sahel, where the Alliance of Sahel States (AES), uniting Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger, now represents a formalized, mutual-defense-backed rejection of traditional governance.

Yet, as this new axis of military power solidifies with Russian backing, a crucial, counterintuitive question emerges from the shadows of these barracks: what happens to the people living next door? When the news of a coup flashes across the border, does it breed imitation, or does it forge a fiercer loyalty to democracy itself?

The numbers tell a brutal story. According to the Coup d’État Project (Colpus) and Global Instances of Coups databases, Africa has witnessed at least twelve successful coups and eight failed attempts across nine countries since 2020, concentrating heavily in West and Central Africa. Mali alone recorded three coups in three years. Chad, Guinea, Gabon, and Niger joined the cascade, while Sudan plunged into civil war following its 2021 military takeover.

Democracy’s Hollow Promise

The most dramatic incident of 2025 came in early December, when soldiers briefly seized state television in Benin, announced the suspension of the constitution, and claimed to have removed the president. They accused the government of neglecting security challenges and ignoring the sacrifices of the military, especially as violence in the north escalated. Their momentum didn’t last, loyalist forces retook institutions and arrested the plotters within hours. But the fact that it happened in Benin, long held up as a stable democracy, says more about the region than the soldiers themselves.

This aligns ominously with citizen sentiment captured in comprehensive surveys. Afrobarometer data reveals that only 52% of Africans perceive their countries as democratic, while a mere 46% express satisfaction with democracy, down from 50% just years earlier. In Nigeria and Eswatini, democratic perception cratered to just 33%. Sierra Leone saw satisfaction collapse by 32 percentage points, the steepest decline recorded across the continent.

Yet the story becomes more complex when examining citizen responses to military takeovers. The UNDP’s groundbreaking “Soldiers and Citizens” report, which surveyed 8,000 Africans in coup-affected states, found approval ratings reaching 80% in Mali for military rule. In Burkina Faso and Niger, popular celebrations greeted the overthrow of civilian governments, framed not as rejections of democracy itself but as desperate demands for reform and security.

Speaking exclusively with Apples Bite International Magazine, Retired General Olumuyiwa Okunnowo, former Nigerian Army commander with extensive experience in regional security operations opined that,

“What we’re witnessing isn’t a wholesale abandonment of democratic ideals,” observes. “Rather, it’s a crisis of delivery. When democratic institutions consistently fail to provide security, economic opportunity, or basic accountability, citizens begin to see military intervention as a necessary disruption rather than an unacceptable deviation.”

Freedom Deficit

The data reveals democracy’s Potemkin facade across the continent. While 73% of Africans claim freedom to vote according to Afrobarometer surveys, barely 51% feel completely free to speak. In Nigeria, only 28% report unrestricted expression, lower than Zimbabwe during its darkest authoritarian years. In Eswatini, 73% report zero freedom to associate politically.

Elections happen, but legitimacy doesn’t follow. Only 70% trust election integrity, plummeting to 46% in both Ghana and Nigeria, countries once considered democratic strongholds. ACLED data tracking political violence shows a direct correlation: in 26 of 30 African countries surveyed between 2011 and 2021, support for elections declined as economic hardships, corruption perceptions, and institutional weakness intensified.

Benin wasn’t alone in 2025. Across the continent, the year saw several attempted coups, plots, and tense standoffs. Guinea-Bissau faced an attempt in November. Mali’s Colonel Assimi Goïta extended his mandate to five years, defying ECOWAS transition timelines. Niger and Burkina Faso pushed democratic restoration further into an uncertain future. Some incidents never made international headlines; others were disrupted quietly behind the scenes by intelligence services increasingly vigilant after years of upheaval.

Regional Responses and Nigerian Influence

Regional bodies responded with varying degrees of effectiveness. ECOWAS, under sustained criticism for being too divided or too soft, condemned the attempted takeover in Benin and called for respect for constitutional order. The African Union repeated its zero-tolerance stance, warning that the continent cannot afford further democratic backsliding.

Nigeria’s role in these regional dynamics deserves particular scrutiny. As ECOWAS’s largest economy and most populous member, Nigeria has historically wielded considerable influence in shaping West African responses to unconstitutional changes of government.

“Nigeria’s position has always been complex,” General Okunnowo explains. “As a democracy that has successfully transitioned power multiple times since 1999, we have a vested interest in defending constitutional order across the region. But we’re also acutely aware that military interventions against coup governments can backfire, creating martyrs and deepening anti-Western sentiment that benefits external actors like Russia.”

This tension became particularly acute following Niger’s July 2023 coup. While ECOWAS threatened military intervention to restore President Mohamed Bazoum, Nigeria found itself caught between regional solidarity and practical realities. The country shares a 1,500-kilometer border with Niger, and any military action would have profound economic, security, and humanitarian consequences for Nigerian border communities.

“The Niger situation exposed the limitations of purely punitive approaches,”General Okunnowo notes.”When you have populations genuinely celebrating military takeovers because they see them as liberation from corrupt, ineffective civilian leadership, you can’t simply bomb your way back to democracy. We needed a more nuanced strategy that addressed root causes, insecurity, poverty, governance failures, rather than just treating symptoms.”

Nigeria ultimately advocated for a diplomatic solution, resisting calls for immediate military intervention despite its capacity to lead such an operation. This pragmatic stance, while criticized by some as weakness, reflected a sophisticated understanding of regional dynamics and the limits of coercive power in restoring democratic legitimacy.

Why Soldiers Strike

One theme ran through almost every incident in 2025: the influence of security threats. The spread of insurgencies from the Sahel continues to shake governments from Senegal to northern Ghana. When soldiers are overstretched, underpaid, or feel abandoned, the temptation to reset the system grows. According to ACLED event data, jihadist attacks in West Africa increased 27% between 2023 and 2025, with Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger bearing the brunt of violence that has killed thousands and displaced millions.

Coups feed on crisis. Once officers believe the political class cannot solve the country’s problems, dangerous ideas about military salvation take root. That sentiment surfaced clearly in Benin, where plotters framed themselves as responding to insecurity and the state’s alleged failures. Similar justifications preceded successful coups in Guinea (2021), Mali (2020, 2021), Burkina Faso (2022), and Niger (2023).

The UNDP report identifies three consistent drivers across coup-affected states: deteriorating security situations that civilian governments appeared unable to address; perceptions of endemic corruption among political elites; and economic stagnation that left large populations, particularly youth, without opportunities or hope for improvement.

Yet military regimes rarely deliver on their promises. History shows they often replace one crisis with another: restricted civic spaces, poor governance, weakened institutions, and delayed transitions. No African country has developed sustainably under repeated coups. Chad’s decades under military leadership produced little progress. Sudan’s cycles of military rule culminated in devastating civil war. Even Mali’s celebrated democratic transition in the 1990s followed military rule that left the country fragile and vulnerable to future instability.

The AES: Formalizing Military Rule

The formation of the Alliance of Sahel States in September 2023, and its consolidation throughout 2024-2025, represents something unprecedented: three military governments, Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger, formally confederating under mutual defense pacts, explicitly withdrawing from ECOWAS, and pivoting toward Russian security partnerships.

actors back military regimes.

Third, the threat of future coups isn’t disappearing unless governments confront root causes: weak civilian oversight of militaries, lack of economic opportunity, insecurity that governments can’t address, and political systems that exclude too many citizens from meaningful participation.

Beyond 2025: The Path Forward

Africa is not destined for military rule. But democracy on the continent needs urgent attention, humility, and genuine reform. The events of 2025 have made that clearer than ever.

Some analysts argue for reforms strengthening local governance and reducing overwhelming concentration of power at the presidential level. Others point to the need for better-managed transitions, stronger legislatures capable of checking executive power, and genuine investment in civic education. Electoral systems need reform to enhance legitimacy; judiciaries require independence to enforce accountability; security forces need professionalization to reduce politicization.

“Democracy cannot survive elections alone,” General Okunnowo emphasizes. “It needs institutions that people trust, leaders who respect constitutional limits, and economic systems that deliver tangible improvements in citizens’ lives. Without these foundations, we’ll continue seeing military interventions framed as necessary corrections to democratic failures.”

The challenge for 2026 and beyond is whether governments can learn from this year’s warnings. If they reinforce democratic institutions, address insecurity with seriousness, make political systems more inclusive, and tackle the corruption and inequality that fuel public frustration, the cycle can be broken.

If not, the conditions driving coups will remain in place. The data is unambiguous: as democratic satisfaction withers and coups proliferate, 2026 signals not aberration but acceleration, a continent where barracks increasingly eclipse ballot boxes, and citizens, exhausted by democracy’s unfulfilled promises, grow dangerously ambivalent to its disappearance.

As 2025 ends, the continent sits at a crossroads. Africa’s coups are not just military events; they are political signals revealing where states are fragile, where citizens feel unheard, and where institutions struggle to meet the demands of fast-changing societies. But they also show that resistance to unconstitutional rule remains strong, from civil society, from parts of the military committed to civilian control, and from regional organisations that refuse to normalise takeovers.

The question now is whether Africa’s democratic promise can be renewed before it disappears entirely beneath the weight of justified frustration and military opportunism. The answer will shape not just 2026, but the political trajectory of an entire generation.

Be the first to comment