UNDERCOVER: With Police, Army On Your Side, You Can Also Become An Illegal Crude Oil Bunkerer

By ‘Fisayo Soyombo

Investigative journalist ‘Fisayo Soyombo spent three months in 2024 embedding himself with illegal crude oil bunkerers, hoping to unravel the delicate network of oil thievery with entrenched roots in the South South and branches all over Africa’s largest producer of the resource. The expedition may have been abruptly terminated by an arrest at a crude oil bunkering site, but it had progressed enough to establish the complicity of the military and the police in terrestrial theft of crude oil.

Under the cover of darkness in Port Harcourt on Wednesday September 19, 2024, two completely different gentlemen — one laconic, the other garrulous — join me at the bar of a hotel in the city centre, to discuss ‘business’. We would be stealing crude oil, the bulwark of Nigeria’s economy, for onward loading to either Enugu or Kano where it would be sold for not just huge but instant profit. The meeting was brief, in fact shorter than the duration of the trip I made to consummate the appointment: we dispersed within 45 minutes of convening, meanwhile I had flown 1 hour and 10 minutes or thereabouts from Lagos.

This was all according to plan: the meeting was merely to set the tone, to ascertain my seriousness in investing in the business, to receive assurance of their competence to pull off the deal and, of course, to put a face to my name. It was the first and only time I ever saw one of them; the other, meanwhile, would become my ‘business partner’ for the next three months.

Reconvening on Thursday October 24, 2024, came with a slight personnel change. Nasiru had replaced the laconic fellow with Henry, a tall, handsome ex-footballer, ex-cultist and self-confessed ex-killer whose contacts in oil bunkering ran so deep he could organise crude theft with both eyes closed.

BUYERS OF STOLEN CRUDE ‘ALL OVER NIGERIA’

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aTtD-V3QXs8?si=b8PoP8mwaGB8t9Ek

“If you load crude onto one truck, 50,000 litres of crude, you need a buyer. I have buyers in all of Nigeria,” Henry says with unflinching confidence, everyone more willing to spill this time. “I can link you. You may be headed to Enugu and I tell you ‘stop in Umuahia; I have a buyer for you’. All you need is ‘here’s my market, where’s your money’? You understand?”

Henry pauses for a while, gazes at me then Nasiru, downs a glass of alcohol, then resumes from where he stopped.

“Where do you want to sell? Enugu?” he asks rhetorically. “I have buyers in the whole Nigeria [sic]; I can link you. As long as it’s oil, there are buyers. Slush? There are buyers. Slope? There are buyers.”

It is unclear what Henry refers to as “slush”. It can be ‘slushing oil’, a semi-solid grease used as a protective, rust-preventive coating for metal surfaces, or ‘oil sludge’, a gel-like or tar-like deposit of contaminated, broken-down oil that can form in engines.

“There are buyers for any oil product, so if it’s about making your money, you will,” Henry continues, brimming with confidence. “All you need is to pray for the business to be successful.”

But this is a risky venture. What factors could possibly impede the success of the ‘business’? Henry identifies security agencies as the single biggest threat but assures me his “colleague” Nasiru “has the whole security” [sic] in his pocket.

“He works directly with the security,” Henry reiterates.

By “security”, Henry means the Nigerian Army, the Nigeria Security and Civil Defence Corps (NSCDC) and a team from the office of the Inspector General of Police (IGP), Kayode Egbetokun, widely known in bunkering circles as the ‘IGP Squad’.

“Even at the loading points, nobody can dare Nasiru’s work because they know his connection,” says Henry. “The army, the IGP team and civil defence are the three security agencies that disturb [sic]; he has the army and the civil defence. But I can take care of the IGP’s team. If you want to load the product from here to Abuja, in terms of IGP, I give you 100% [sic].”

Really?

“IGP, the whole Nigeria [sic], I can clear that one,” he insists. “That’s my strength.”

FIJ subsequently established from multiple police sources that the police unit colloquially known as the ‘IGP Squad’ is indeed the Inspector General of Police Special Task Force on Petroleum and Illegal Bunkering (IGP-STFPIB), a unit dedicated to combating oil theft, pipeline vandalism, and illegal bunkering activities. IGP Kayode Egbetokun restructured this team at about the time I was planning my first Port Harcourt trip, appointing Deputy Commissioner of Police Bayonle Sulaiman as the new Commanding Officer in July 2024.

During that announcement, Egbetokun also decried the significant threat of oil theft, pipeline vandalism and illegal bunkering to the environment, economy, and energy security, noting: “these illegal activities not only result in significant financial losses but also devastating environmental consequences, including oil spills, pollution and habitat destruction”.

AN EVERLASTING STRUGGLE

Nigeria has always struggled with maximising its immense crude oil wealth. A few months before Egbetokun’s announcement, the Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission (NUPRC) had revealed a 7% drop in the average crude oil production from 1.32 million barrels per day (mbpd) in February 2024 to 1.23 million bpd in March, marking the second consecutive month-on-month decline after a two-year high of 1.43mbpd in January 2024.

In October 2025, the Nigerian Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (NEITI) lamented that the Federal Government lost a total of 13.5 million barrels of crude oil worth $3.3 billion to theft and pipeline sabotage between 2023 and 2024. Meanwhile, an October 2025 report by the Fair Finance Nigeria (FFNG) coalition revealed that Nigeria lost about 619.7 million barrels of crude oil valued at $46.16 billion to theft between 2009 and 2020. The report, titled ‘Community Voices on Oil, Finance, and the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA): A Case Study of Akwa Ibom and Bayelsa States’, launched in Abuja, revealed the enabling industrial-scale crude oil theft by weak regulation, systemic corruption and the complicity of some security agencies and oil companies.

The consequences of these losses are damning. In 2024, for example, Nigeria failed to meet its oil production target of 1.78 million barrels per day, consequently hampering the government’s ability to finance its budget and worsening the country’s already atrocious debt profile. Meanwhile, President Bola Tinubu’s N47.90 trillion 2025 ‘budget of restoration’ is benchmarked against a base crude oil production assumption of 2.06mbpd!

THE MATHEMATICS OF BUNKERING

The conversation with Henry and Nasiru soon eases to the financials of the enterprise. Renting a truck to convey the stolen crude from Port Harcourt to Enugu would cost a minimum of N3 million under perfect conditions — a down payment of N1 million, an additional N1.5 million after stealing the crude, a final N500,000 after emptying it to the buyer. If we rented the truck but failed to lift the crude and return the truck within three days, I would incur demurrage that could eventually total N4 million to N6 million. I hoped for the best.

The ‘businessmen’ with access to crude lines from the pipeline planned to sell to us at N320/litre. This, multiplied by the 50,000-litre capacity of the truck, amounted to N16 million. Henry’s clients in Enugu were hoping to buy for N550/litre, amounting to N27.5 million and leaving us with a profit margin of N8.5 million under perfect conditions. If we ended up in Nsukka, sellers would take the crude for N600/litre, amounting to N30 million in costs and N8 million in profit.

“The problem with Abakaliki, they can say they don’t have cash,” Henry warns. “But Enugu always has. Abakaliki will tell you to park your truck [and wait while they go looking for cash]; this is risky, so it’s better to discharge in Enugu and collect your money.”

We fiddle with the idea of Kano as well. Kano promises far more mouthwatering profit than the already enticing Abakaliki. It also offers the prospect of establishing the entrenchment and ubiquity of the oil thieving network. The problem, though, is that the longer a truck travels on the road, the slimmer its chances of evading arrest. We abort it.

“If they load today and we move at 6 am, by 2 pm you’re already in Enugu. In fact, with a fast-moving truck, you can be in Enugu by 1 pm,” Henry adds. “But once they return, everyone spends the next two days strategising. We may even reshuffle our workers. Everything is just about wisdom.”

Our interaction is interrupted by an incoming call to Nasiru’s phone. The caller, according to Henry, is “a superintendent of police”. “That’s not a small man,” he says, “and that’s to show he has security covered.”

We iron out a work plan. I had until 7 am on Friday October 25 to confirm my intention to proceed. If I did, a truck would be secured to load crude from the pipeline on Friday or Saturday night.

I didn’t reach out to them for days. I first needed to go find N22 million.

FINDING N22 MILLION THAT COULD GO DOWN THE DRAIN

Finding N22 million was far from an impossible ask; the real problem was that the entire sum would go to waste unless the operation progressed to perfection. And even if it was successful, the costs of incidentals would surely be unrecoverable. It has happened before. When I tracked Arrows of God, an orphanage home that sold babies under the table to willing buyers, for 19 months between 2021 and 2023, the N2 million I paid to buy a four-month-old baby was never recovered for me by any institution — not the police, not the National Agency for the Prohibition of Trafficking in Persons (NAPTIP), not the Lagos State Ministry of Youth and Social Development that is now in possession of the baby.

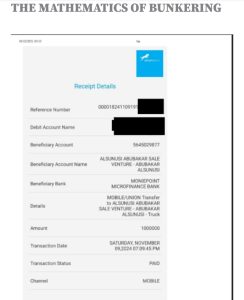

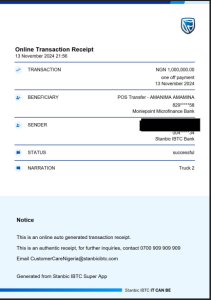

When I rang Nasiru in the first week of November to announce my readiness, he instructed me to pay N1 million as “proof of your seriousness” to nail down a truck. I made this payment on November 9, 2024, then hopped on the next available flight from Abuja to Port Harcourt.

NOVEMBER 13, 2024: ‘YOU CANNOT FOLLOW THE TRUCK’

Four days later, it is time to move. Nasiru rings me as dusk falls, asking me to meet up with him and Henry at Dream Plaza, Arabanko. There, a bunkerer by the name ‘Alhaji Mohammed Adamu’ was waiting. All three gobble monstrous molds of swallow and step it down with alcohol of varying brands as we start to strategise for the night. I opt for two wraps of garri and a bottle of Maltina.

I panic a little when Alhaji objects to my presence on the truck. Reason: his people would be uncomfortable with a strange face on the truck as they steal the crude. I plead my case, even subtly suggesting I would pull out of the deal if they wouldn’t let me in. “My brother tried something similar with Associated Gas Oil (AGO) in Delta. He trusted people with money without being physically present, and he was duped,” I argue. “I don’t want to suffer a similar fate. If I won’t be there, I’m afraid I’ll have to discontinue the deal.”

Alhaji reluctantly agrees. By then, the truck had arrived. I step out to inspect it. I do not know what to make of the engine but the body is long and big, just like its rotund owner Amanima Amamina, a well-built middle-aged man with a protruding belly. Amamina is fairly popular and respected in the community; he owns a chain of businesses, including a hotel, but I suspect his most lucrative source of livelihood is bunkering. He appears to possess deep contacts in the cartel and in security as well. Some of his trucks had been burnt by stubborn security agents in the past, but every single one they burnt he replaced; the business is that lucrative.

We set out from Arabanko at exactly 10:25 pm; this was when I first noticed the truck crawled and would lose a racing contest with a snail. Well, I exaggerate.

The driver parks somewhere around Indorama Eleme Petrochemicals Limited at exactly 11:18 pm. Nasiru and Henry abandon me there, climbing into their two-door car with a promise to return whenever I got the green light to load. That never happened. After more than four hours of being mercilessly feasted upon by mosquitoes as I sat in the truck, we were told it was an ill-advised night to operate.

TRUCK PROBLEMS FOR THE UNION TO RESOLVE

The surroundings of our crude oil target

By November 18, we had encountered more pressing problems than mosquitoes. Amamina, whose truck we had secured since November 13, wanted more money. Nasiru had paid him N1.5 million from my N2 million deposit, but after five days Amamina determined that the payment had expired.

“You didn’t tell me you were planning to load at Pipeline,” he fumes. “[At] Pipeline, [there is] no mercy if you don’t ‘do your settlement well.’”

“If you want to go to Pipeline,” he continues, “give me a cheque of N50 million and transfer another N10 million to me.”

Henry howls in agony, Nasiru gnashes his teeth in disagreement. Still, Amamina would not budge.

“That money you gave me is gone,” he insists. “The truck has not been with me for five days. My diesel of 400L has been stolen; the truck’s tyres are deflated. Now that they have confessed that they want to go to Pipeline, they must give me N10 million in cash and another N50 million in cheque.”

Henry and Nasiru are vehement in their disagreement. Nasiru’s proposition is to forfeit only N500,000 of the N1.5 million and reuse the truck. The two-hour meeting with Amamina features shouting matches in swathes and ends up deadlocked. The pleading duo vow to table the matter before the ‘union’. A union of illegal crude oil bunkerers? That was a jarring discovery.

Source: https://fij.ng/article/undercover-with-police-army-on-your-side-you-can-also-become-an-illegal-crude-oil-bunkerer/?s=08

Be the first to comment